National News

All the latest national news, sport and entertainment stories from our newsroom.

Asylum Seekers Moved Into Military Barracks Amid Pressure To End Hotel Use

The first asylum seekers have been moved into a former military barracks in East Sussex as ministers face pressure to end the use of hotels..

Ex Labour Minister Says He Is Standing Down As MP For Medical Reasons

A former Labour minister has announced he will stand down as an MP for medical reasons, paving the way for a potential Westminster return for Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham..

Jessie Buckley Scores Oscar Nomination While Sinners Makes History With 16 Nods

Irish actress Jessie Buckley has been nominated for an Oscar, while vampire drama Sinners has made history as the first film to score 16 nods..

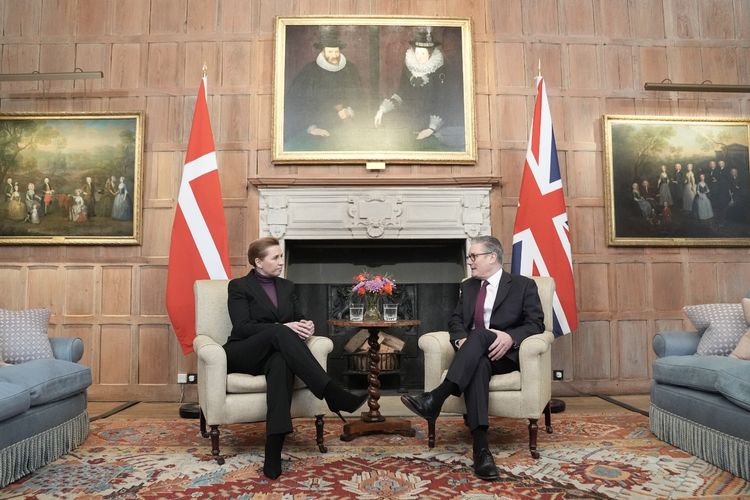

Keir Starmer And Danish PM Discuss Vital Steps Towards Arctic Security

Sir Keir Starmer said he will discuss how to “take the vital steps” towards strengthened security in the Arctic with Denmark’s prime minister, who thanked him for the UK’s support during “quite a difficult time” for the country amid Donald Trump’s demands to annex its semi-autonomous territory Greenland..

Harry Returns To Court After Giving Evidence In Trial Against Mail Publisher

The Duke of Sussex has returned to a court in London for the fourth day of the trial of his legal action against the publisher of the Daily Mail..

One In Four Children Starting Reception Not Toilet Trained Survey Finds

Around one in four children who started reception in 2025 were not toilet trained, a survey of teachers has found, amid warnings more children are struggling with basic life skills..

Sean Bean To Host Birdwatching Podcast

Hollywood star Sean Bean is to host an award-winning podcast for birdwatchers..

Substantial Increase In ADHD Prescriptions Driven By Women Study

There has been a “substantial increase” in the proportion of people using medicines for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the UK, driven by a rise in prescription rates among adults, in particular women..

33 Russell Bromley Stores At Risk After Next Buyout

Next has bought Russell & Bromley after the footwear and handbag retailer fell into administration..

Mother Of 10 Found Guilty Of Keeping House Slave For 25 Years

A teenage girl was forced to work as a “house slave” for a woman and her 10 children for more than 25 years, a court heard..

Inflation Bounces Back In December As Christmas Travel Fuels Price Rises

UK inflation bounced back in December as tobacco duty hikes and Christmas getaways helped push up the cost of living, official figures show..

Donald Trump Doubles Down On Greenland Threat But Rules Out Using Force

Donald Trump has doubled down on his threats to annex Greenland, saying only the US could secure the Arctic territory, but ruled out using force..

Reeves UK Will Not Be Buffeted Around Amid Trump Tariff Threats

The UK will not be pushed around by Donald Trump’s tariff threats, Rachel Reeves said as she defended Sir Keir Starmer’s attempts to cool tensions over Greenland..

Landmark Study Paves The Way For Type 1 Diabetes Screening Among Children

NHS pre-diabetes clinics for children are to be set up after a “landmark” study confirmed the feasibility of using finger-prick blood test as a screening tool to spot the disease before symptoms arise..

Ads For Sunbed Firms Banned For Misleading And Irresponsible Safety Claims

Adverts for five tanning companies have been banned for making misleading and irresponsible claims about the safety of sunbeds..

New Stamps Mark 50th Anniversary Of First Commercial Concorde Flights

A new set of stamps and coordinated nose drop events will mark the 50th anniversary of the first commercial Concorde flights..

Police Hit Back At Decision Not To Bring More Charges Against Nurse Lucy Letby

Police have hit out at the decision not to bring further charges against child killer nurse Lucy Letby..

Under 16s Social Media Ban And Overnight Curfews To Be Considered Liz Kendall

Overnight curfews and breaks to prevent “doomscrolling” will form part of the Government’s consultation on social media for children, which will also consider an Australian-style ban for under-16s..

Chinese Embassy Plan Approved By Government

China has been given permission to build a vast new embassy in the heart of London despite criticism from MPs and campaigners that it will be used as a base for spying and security crackdowns..

Wage Growth Falls As Unemployment Stays At Highest Level For Nearly Five Years

UK wage growth has fallen back once again while the unemployment rate has remained at the highest level for nearly five years as official figures reveal deepening jobs woes in the retail and hospitality sectors..

Local News

Community fund offers £18,000 for new projects and local support

Charities and not-for-profit groups have the chance to secure funding for community projects.

MP welcomes new £200m government SEND training scheme

Chris Ward MP for Brighton Kemptown and Peacehaven has praised government for announcing a £200 million landmark SEND teacher training programme.

Dark Skies Festival marks a decade of wonder above the South Downs

This year’s Dark Skies Festival will mark 10 years since the South Downs National Park was designated as an International Dark Sky Reserve.

Entrepreneur’s spiritual business earns global award nomination

A Brighton-based businesswoman has been nominated for a global award recognising new businesses led by women.

Former care home will be turned into flats

Plans to convert a former care home and day care centre into 17 flats have been approved by Mid Sussex District Council.

Businesses invited to share views on cost-of-living pressures

Chichester businesses are being invited to share their views.

Popular fast-food chain to open newest branch in Sussex town

Mexican chain Taco Bell is opening its latest store at 10 Grand Parade, Crawley, on January 23, 2026, following years of delays.

Free event to offer expert insight into breast reduction and uplift

A free information session about breast reduction and uplift surgery will be held in Brighton.

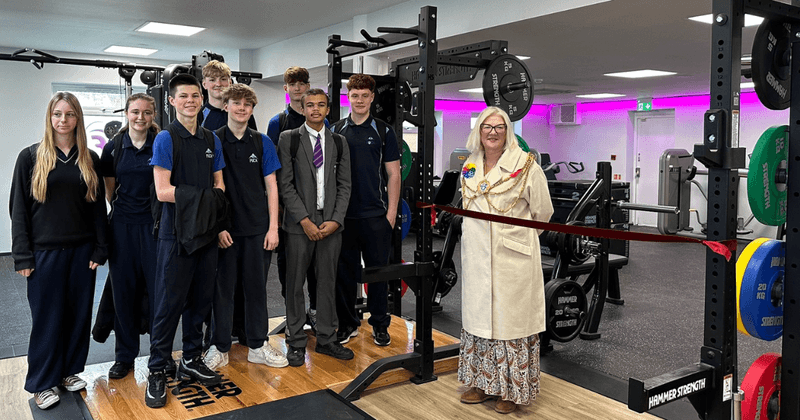

Gym nearly doubles in size after major revamp and expansion project

The new look gym at Portslade Sports Centre has been officially opened by Mayor Amanda Grimshaw

New cycle parking to be installed after successful bid

The new racks will be installed at the junction of Brunswick Road and St Mary’s Road, and in New Road, following a successful Community Highways Scheme bid

Plans for new crossing near secondary school 'should prioritise children'

A proposed new crossing in Old Shoreham Road should prioritise children, according to a councillor and school governor

Hospital to undergo vital work to address major structural concerns

St Richard's Hospital in Chichester is one of 41 hospitals in England with confirmed reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac)

Council tells residents to be more kind and respectful as it launches a campaign

Mid Sussex District Council has launched a new initiative aimed at fostering kindness, respect and building a supportive community for staff and residents

Concerns raised as takeaway wants to deliver until 5am

A takeaway wants to offer deliveries until 5am but Sussex Police and Brighton and Hove City Council’s licensing team have objected

'Special' Sussex coffee shop with 'great pastries' named among best in the UK

The Best Coffee Shops in the UK group has revealed its picks for the top spots across the country, with this spot in Sussex highlighted.

Residents say road being used as a 'rat run' is 'nerve-wracking' for drivers

Concerns around an Eastbourne road being used as a “cut through” have been heard by a senior county councillor

Renovation plans submitted for historic cottage after heavy metal legend's plea

The plans, involving Blake's Cottage, in Felpham, near Bognor Regis, would see the introduction of a new main staircase and the building of a visitor centre

Victory for objectors amid plans to build shop and flats on pub garden

The plans for The Prince Albert pub on Copthorne Bank included the partial loss of the pub’s garden to make way for the new development

Plans for more than 1,000 homes are delayed as council tries to catch up

The regulations, which had been enforced since 2021, had prevented any development that increases the overall use of water in Crawley from progressing

Neighbour threatened to kill retired railway worker as row boils over

An ombudsman has ordered Brighton and Hove City Council to pay compensation to a retired railway worker living in sheltered housing in a row over a neighbour who threatened to kill him